The Psalms inform us that, “Each man’s life is but a breath.” Without breath, our lives would be impossible. The exchange of oxygen for carbon dioxide in the lungs is certainly essential for the human being to function, but it is not air that keeps us alive. Rather, human beings are sustained by an extremely powerful form of subtle energy known as prana that accompanies the air we breathe.

Traditional Western medicine defines humans as primarily physical beings. This approach logically evolved from a cultural attitude that characterizes each person as a separate, quantifiable entity. Reflecting the habits of the human mind, medical science has, until recently, limited its scientific inquiry to the perceivable and quantifiable.

Albert Einstein wrote that “a problem cannot be solved on the same level at which it arose.” This open-minded attitude helped him recognize that in the material universe an essential relationship exists between matter and energy. More specifically and scientifically, E=MC2 (energy is equal to the mass of an object, times the speed of light, squared). In practical language, Einstein is telling us something profoundly important for our own health and well-being. He says that matter, the material stuff of the universe, can be transformed into energy, and that energy, conversely, can be turned into matter.

Our everyday experiences and observations have already taught us that energy and matter are one and the same. For instance, we count on the oatmeal we eat for breakfast to be turned into the energy with which we accomplish our work. With each bite of cereal, we are betting our lives that the energy of the sun (now contained in our oatmeal) will be reliably transformed into the carbohydrates and proteins our bodies and brains need to function. We accept without question that the calories (energy) we consume will become the physical bodies we inhabit and give the body strength to act. Such obvious and verifiable examples of the transformation of energy into matter, and matter into energy, did not become more true after Einstein’s mathematical equation was stated, but his work has provided an interface between ancient assumptions about prana and modern physics.

Prana and the Nadis

In Sanskrit, the word prana refers to the first unit of life, a subtle energy emanating from the soul (Sat-Chit-Ananda) and flowing within the living human being. On the most subtle level, it is the vital prana that animates the body-mind-sense complex. If you forced air into the lungs of a cadaver it would not get up and walk away. Why not? Because it is the prana already present in a living body that invites, receives and distributes the life force of prana carried on the vehicle of breath. It is prana alone, not the mediums of air, food, or water, that enlivens the body.

The human body is maintained by an intricate network of subtle rivers of energy, through which the vital prana flows. These rivers are called nadis, and the aggregate complex of nadis and prana are known as pranamaya kosha. This body of energy is subtler than the physical body and serves as a link between the mind (manomaya kosha) and the physical body (annamaya kosha). Thus, the energy sheath of prana can influence both the mind and body, and is influenced by them as well.

Pranayama (Control of Prana)

The breath is the body’s primary delivery system for the vital prana. The relationship between the air we breathe and prana is analogous to the relationship between a horse and its rider. Just as the horse is the vehicle for the rider, the air is the vehicle for the prana. The air merely carries the prana to its destination in the physical body.

Prana means the first unit of subtle energy and yama means control. Pranayama is the science that controls the prana, primarily by breath regulation. Breath awareness exercises help to normalize the motion of the lungs––thereby assuring the direct and balanced flow of this subtle energy to sustain and coordinate all the body’s physical and mental functions. Without such regulation, the intended flow of pranic energy can become trapped, eventually manifesting as physical, mental or emotional dis-ease or pain. Without a continuous delivery of vital prana, the respiratory system, the heart, the brain and autonomic nervous system do not function in a well-coordinated manner. Disturbances in these physical processes can result in serious illness. Such blockages also limit progress in meditation.

In pranayama, the breath is considered to be the bridge between the body and the mind. Concentrated attention on the breath affects and directs the flow of the vital prana through the body. Every time we think about moving a part of the body, for example, vital prana rushes toward that site along the subtle network of nadis to make movement possible. Conversely, bodily movements also affect the flow of prana. A regular Easy-Gentle Yoga practice, therefore, is an essential element in maintaining and gently moving the vital prana.

Respiration is the body’s primary mechanism for the strategic flow of energy. Inhalation and exhalation determine the rate, rhythm and depth of the breath thereby impacting the amount of energy available to the body and all the metabolic processes. The breath determines whether energy is delivered in irregular, short bursts or in longer, more sustained waves. With every breath we are redefining the patterns of energy that affect both the body and the mind––for better or worse.

Breathing air deeply into the lungs is a critical factor in maintaining good health. Diaphragmatic breathing calms the nervous system while massaging and stimulating the heart and all organs of digestion and elimination. In addition, it efficiently oxygenates the blood. Oxygen is inhaled into the lungs where it is transferred into the bloodstream for distribution to all the cells of the body. Because the human torso is carried in an upright position, gravity generally acts to keep greater quantities of blood in the lower portion of the lungs than the upper. With deep, diaphragmatic breathing, the lungs fill to their capacity, providing oxygen to the lower lungs where it can most readily be absorbed. Those who breathe shallowly, moving only the upper chest, often feel fatigued. Their improper breathing habits inhibit the process of oxygenation and deny vitality to the cells of the body.

Breath and Mind Connection

The breath is the physical manifestation of the mind. Although we cannot intellectually will the mind to calm down, we can create a serene, contented mind through conscious regulation of the breath. When our breath is full and even, without jerks, pauses or sounds, our minds become calm.

Through your own personal experience you may already know that the rhythm, rate and capacity of your breathing changes instantly in reaction to your thoughts, desires and emotions. When you are tense or surprised, you may hold your breath. When you are stressed, the breath may become rapid or shallow. When you are happy and content, the breath reflects that state of mind with its fullness and ease.

Five Breathing Irregularities

Most pranayama should be practiced in your regular seated meditation posture with your head, neck and trunk straight. Once you have established a comfortable and steady posture, you may notice one or more of five possible irregularities in the breath.

1. Shallowness of breath

2. Interruptions in the flow of breath (jerks)

3. Noisy breathing

4. Extended pauses between your inhalation and exhalation

5. Breathing through the mouth

Diaphragmatic Breathing

To correct any irregularity, simply witness it with relaxed attention. This correction is the natural effect of your conscious attention to a formerly unconscious habit.

When you breathe diaphragmatically and deepen your meditations, you will begin to recognize that most seemingly involuntary movements of the body are actually results of thought or emotion. When you observe your physical behavior, you will notice that no act or gesture occurs independently of the mind. The mind always moves first and then the body follows. The untrained mind often dissipates vital prana through nervous bodily movements and twitches––energy that could better serve you in health-enhancing ways.

When the breath flows freely, smoothly and silently through the nostrils without any jerks, pauses or sounds, the mind experiences a state of joyful and calm stillness. This mental stillness frees the mind to make conscious, discriminating lifestyle choices that bring health and happiness.

In properly regulating the breath, never extend the breath beyond your comfortable capacity by inhaling or exhaling as much air as possible. With continued practice, your capacity will increase, but this should not be rushed. Rather, learn to turn your conscious attention toward establishing a gentle, full and even diaphragmatic breath.

The goal of the science of breath is to re-establish the body’s natural respiratory pattern––not by breathing from the upper chest, which is an unhealthy habit, but rather, by consciously employing the diaphragm, one of the body’s strongest muscles, in your breathing process.

The Complete Yogic Breath

A full and smooth diaphragmatic breath is composed of three distinct, yet seamlessly integrated phases of inhalation: abdominal, thoracic and clavicular.

A newborn baby naturally uses the abdomen to breathe diaphragmatically. To feel the first phase of proper diaphragmatic breathing, imagine a balloon positioned just behind your navel. When you inhale, the balloon inflates and your belly gently swells outward. When you exhale, the imaginary balloon deflates and the belly contracts gently.

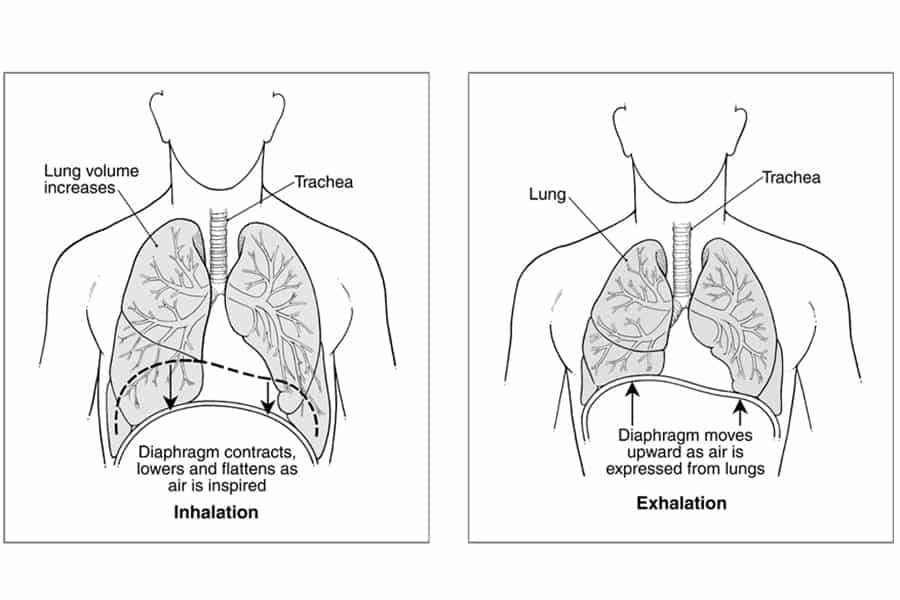

Abdominal phase: In its resting state, the diaphragm physiologically resembles the dome of an open parachute. Proper inhalation begins when the belly swells slightly––causing the diaphragm to flatten downward into a disk-like shape, expanding the thoracic cavity and facilitating inhalation. Exhalation follows more or less automatically when the belly gently contracts––causing the diaphragm to relax and rise to its resting dome shape, compressing the lungs.

Thoracic phase: After the abdominal phase, the belly expands outward and the lower ribs expand upward and forward, enlarging the thoracic cavity and increasing the circumference of the chest. The lungs fill this increased space, permitting oxygenation of blood in the lower lungs.

Clavicular Phase: In the final phase of the inhalation the clavicles (collar bones) rise slightly, allowing oxygen into the upper portions of the lungs.

When all three phases of diaphragmatic breathing are integrated into one continuous motion, the breath becomes the flywheel for a healthy mind and body. A full, smooth, quiet diaphragmatic breath should become your default breath.

In this ideal breath, all inhalations and exhalations flow through the nostrils rather than the mouth, and the entire process is without noise. If you are breathing rapidly and shallowly, or holding your breath between exhalation and inhalation, you are probably chest breathing. The inhalation and exhalation should gently yield to each other.

The fast pace and stress of modern life (and tight pants, belts and pantyhose), have contributed to the unfortunate fact that most people experience nearly constant tension in the abdominal muscles. In addition, concerns about having a fashionably flat, hard abdomen keep many people pulling in their gut, military style. By not allowing the breath to be full and complete, you’re utilizing only a fraction of your lung capacity.

Dangerous Breathing Patterns

Chest breathing is a dangerous habit. It tenses the body and disrupts the normal breathing rhythm that can, long term, damage the heart and brain. Furthermore, it retards a complete exchange of gases through the lungs. Chest breathers never fully empty their lungs. Toxins that remain in the trough of the lungs are reassimilated through the semipermeable membrane of the lungs’ lining, taxing the body and compromising the immune system.

Because the breath reflects our state of mind, a frenetic lifestyle is often accompanied by uneven breathing. Recent studies have found that a pause in the stream of breath, or holding the breath, is often associated with both coronary heart disease and dementia in the elderly.

When we breathe diaphragmatically, the heart muscle performs its duties with calm efficiency. But when we react unskillfully to fear, anger or greed, muscles immediately contract and the shoulders hunch forward, compressing the chest in a posture reflecting the dis-ease in the mind. Under stress, the body abandons its natural, diaphragmatic breath in favor of the shallow, uneven and often rapid inhalations of chest breathing, and the subsequent shortage of oxygen in the blood quickly becomes problematic.

The heart reacts immediately to this crisis. “Something’s wrong,” the heart concludes. “We’re not getting enough oxygen. I’d better change the normal rhythm of my beat. Perhaps a faster beat will help move more blood through the lungs to access oxygen and bring this fellow back to a more composed state.” But, of course, the elevated heart rate only makes matters worse, increasing stress on the heart muscle and vascular system and decreasing their efficiency while sparking further anxiety. Chest breathing accompanied by jerks and pauses in the breath may also be the beginning of a form of significant dis-ease––coronary heart disease.

Eliminating the pause between inhalation and exhalation, and between exhalation and inhalation is an important aspect of proper yogic breathing because it helps you keep a balanced mind and healthy body. The breath should become one continuous, unending stream in which the inhalation gently yields to the exhalation and the exhalation gently yields to the inhalation.

Full and even diaphragmatic breathing constantly massages the internal organs. This rhythmic motion transmits beneficial messages to the entire autonomic nervous system, encouraging all systems within the body to operate optimally. A smooth diaphragmatic breath, not beyond your comfortable capacity, acts as a calming lullaby for the internal organs, while chest breathing invariably sends signals that some sort of crisis is at hand. Chest breathing is not only the result of anxiety, but can also be its cause.

Diaphragmatic breathing aids digestion, assimilation of essential nutrients and the elimination of waste products from the body. Whenever possible, cultivate the habit of loosening your belt and the waistband button of your pants at mealtimes to encourage deep, full breathing. By consciously incorporating the eating and breathing processes into your everyday life, you will enjoy your food more completely and the body will readily demonstrate its appreciation by exhibiting good health.

Reprinted from The Heart and Science of Yoga ©2005. All rights reserved.About the author

Leonard Perlmutter (Ram Lev)

Leonard is an American spiritual teacher, a direct disciple of medical pioneer Swami Rama of the Himalayas, and a living link to the world’s oldest health and wisdom spiritual tradition. A noted educator, philosopher and Yoga Scientist, Leonard is the founder of the American Meditation Institute, developer the AMI Foundation Course curriculum, and originator of National Conscience Month. He is the author of the award-winning books The Heart and Science of Yoga and YOUR CONSCIENCE, and the Mind/Body/Spirit Journal, Transformation. A rare and gifted teacher, Leonard’s writings and classes are enlivened by his inspiring enthusiasm, vast experience, wisdom, humor and a clear, practical teaching style. Leonard has presented courses at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, numerous medical colleges, Kaiser Permanente, the Commonwealth Club of California, the U. S. Military Academy at West Point and The New York Times Yoga Forum with Dean Ornish MD.